Innovation is all around us. New products and flashing new programs grace the headlines, from the newest Apple products, to medical and science technology soaring to new heights.

In the creative fields, we often hear about new products and programs, each boasting new ease and promising incomparable results with a tap of the finger or swipe of the screen. These can dazzle, and those of us who do enjoy testing a sleek new device or program can find ourselves drooling at the prospect of something to make our endeavors that much easier, and well, it looks so cool!

Much like those of us captured by the Apple cycle, it can be tempting to seek the newest programs and products with the promise we subconsciously tell ourselves that newer must be better. The trouble is, what if it’s not?

When introduced to a new program, or surrounded by new programs, we need to block out the din of advertising and think critically of its worth. Is this a reliable brand and useful product, or just a fleeting new toy? Will I be able to adapt to the new program with ease? There’s not much use in acquiring a new program if the cost and time of learning it outweighs the benefit. Of course, with the internet, you can look up reviews, and tutorials for that matter, and a good many of them may relate directly to your creative field of choice that can give you an idea of whether it is worth diving in. However, while reviews can be helpful, they should not take the place of self-assessment, in cost and hours that will need to be spent; and most importantly, what’s the point?

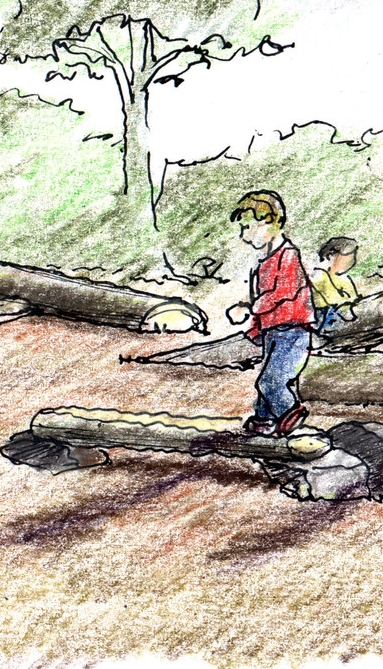

In our office, we’ve begun a communications project, in which we are creating short animations. The goal is to give new life to the documentation of our projects and to enhance our digital media presence. Before getting to that though, we had to establish the narrative, and figure out purpose. Why are we doing this? What do we want the audience to take away, who is the audience? After some discussion we agreed that a diagrammatic animation would best illustrate the design strategies and qualities of this particular project to those who love as well as those who practice architecture.

In this particular case, I was able to choose a program I am comfortable with, but it had me thinking about the nature of programs and their use within the creative fields, and naturally, architecture. Since I was animating, I couldn’t help but think of how animation has found a niche in architecture, most commonly found in the form of sleek and sexy renderings to promote a design in order to win a project. I speculated on this, sometimes drawing parallels to movie trailers, showcasing a building’s design, a flock of birds startled at its beauty, taking flight as the most perfect lens flare glints off the edge of the structure. How picturesque; how epic!

There are numerous articles and debates that can easily be found via Google vouching for or railing against the use of computer generated renderings. The arguments go back and forth about whether these building trailers are helping or hurting, creating unrealistic expectancy in the final product. Examples abound of renderings boasting one thing, the final project squeaking something else.

By comparison, our project is about the design process of a completed building, animated for better understanding, rather than a glamorization of a promise.

While we have no expectations that the use of technology to create ultra-real renderings will diminish, we do hope that animation will sponsor more explorations of process alongside product.

After all, there are good chances that some of these slick renderings and our process animations were created, at least in part, using the same program.

Don’t get me wrong, I love checking out a fancy rendering and they are certainly attractive, but I hope to see more animation in the field, its use varied, and like the new programs popping up, innovated. Animation is the tool of choice for what we are looking to accomplish in this particular project; it’s important to remember that it has endless possibilities. Those possibilities must be assessed on our personal creative needs, before it can come to fruition, or we risk wasting time, money, and effort.

So, before you jump on board to the newest program or device, remember: all technology is a tool, nothing more, nothing less, and it’s how you use it that matters.