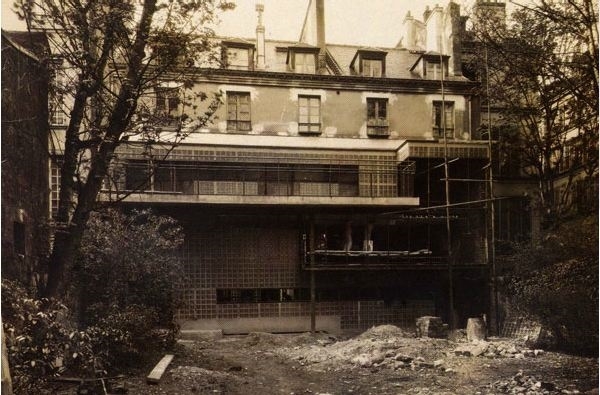

Maison de Verre is a three story building from 1932 tucked away in the 7th arrondissement of Paris. The original owners, Dr. Jean and Annie Dalsace, political socialites interested in the avant garde, wished to create a building housing space for Dr. Dalsace's clinic, their private living quarters, and space to entertain. In true architectural lore form, a serendipitous connection was made between the perfect designer and the perfect client; Annie Dalsace's dance and English tutor happened to be married to The Pierre Chareau.

The iconic image of Maison de Verre's glass block facade lit from within. Image: "La Maison de Verre," published by Thames & Hudson

Pierre Chareau, the "General Designer"

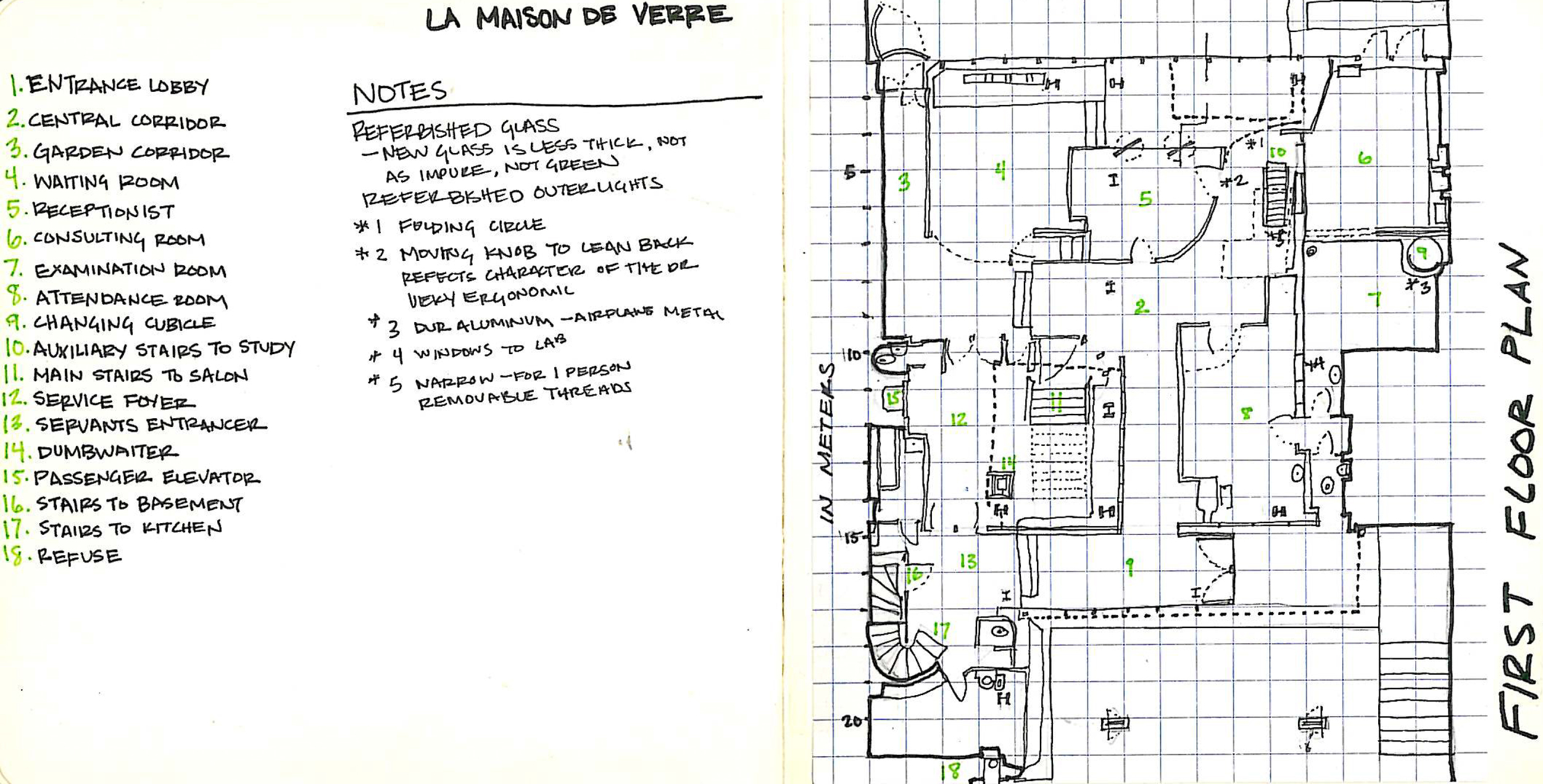

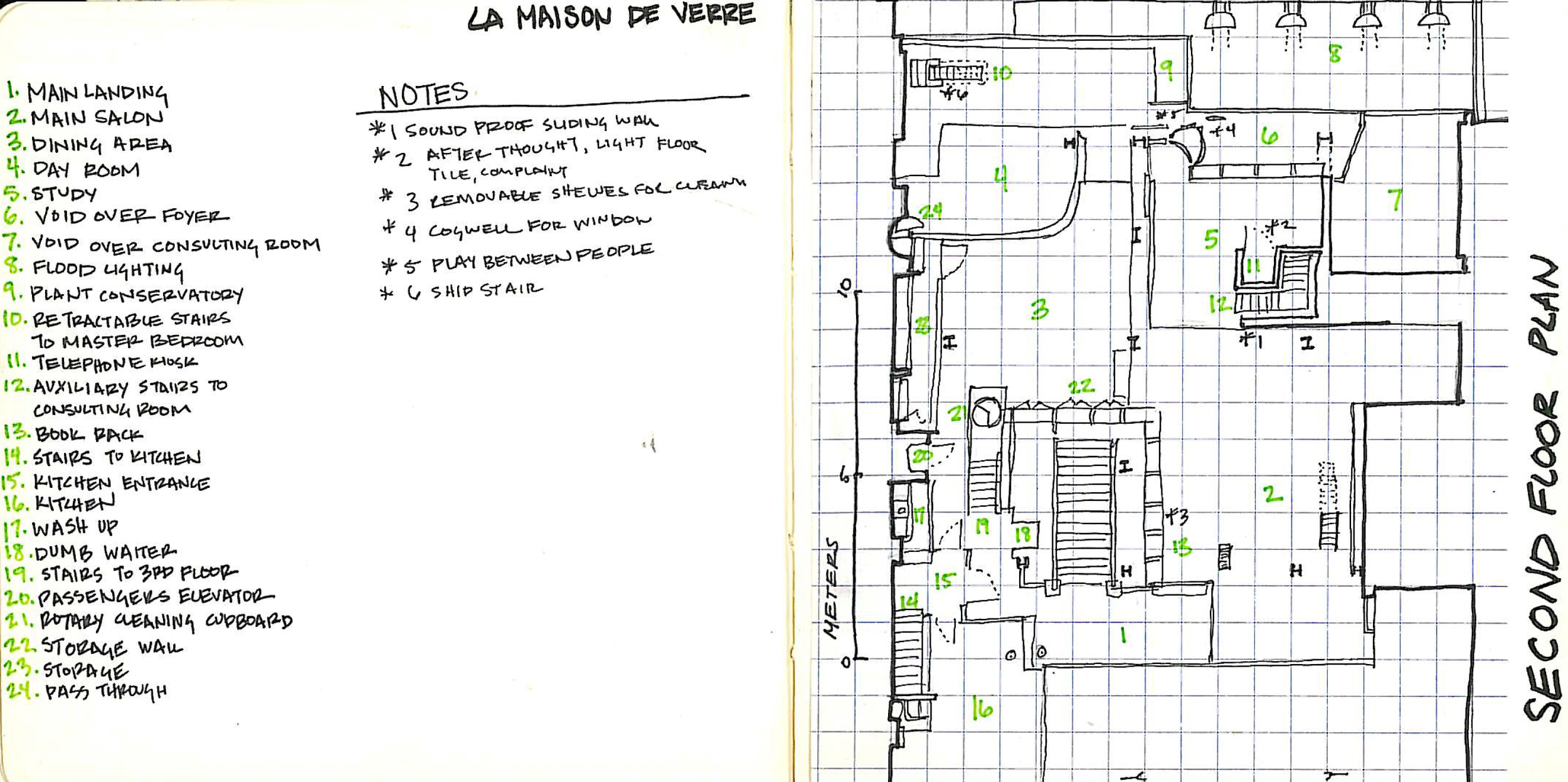

Chareau dabbled in all sorts of design - he started as a draftsman for high end interior architects and yacht designers, later owning his own furniture design firm. Chareau was a member of the Congres International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) but had an affinity for the work of Art Nouveau artisans. For this project, he assembled a collaboration which included Bernard Bijovet, a Dutch architect, and Louis Dalbet, a metal-working craftsman. The three of them spent four years building a home which still resonates to this day; its intricacies are often compared to the inner workings of a clock.

Chareau's career was tragically cut short. He was forced to flee Paris during WWII, ending up poor in New York City where he remained relatively unknown. Hoping to garner new commissions and pique attention for his earlier work, he approached MoMA to exhibit his work. Philip Johnson turned him away. Chareau committed suicide in 1950.

Maison de Verre fared the century better than its "General Designer." It stayed in the Dalsace family for over 70 years and functioned as a medical office until 1994 (!). In 2006, the house was purchased by Robert Rubin, a commodities trader and economist, turned "exuberant and idiosyncratic collector," according to Alastair Gordon's 2011 Wall Street Journal article profiling Rubin. Rubin has tapped architectural historians and grad students in the effort to study and preserve this masterpiece. He is gracious enough to allow those associated with architectural institutions to walk through the house, albeit sans shoes.

In 2009, I had the great fortune of being one of those visitors. The iconic image of Maison de Verre is the cropped, lantern-like facade seen above. In my opinion this is, by far, the least interesting aspect of the design. For your consumption, a photo journal of my Maison de Verre experience:

“Chareau knew how to limit himself and that is why he created a beautiful thing which is the starting point of a true architecture.. . . Pure aesthetic research was not its goal”

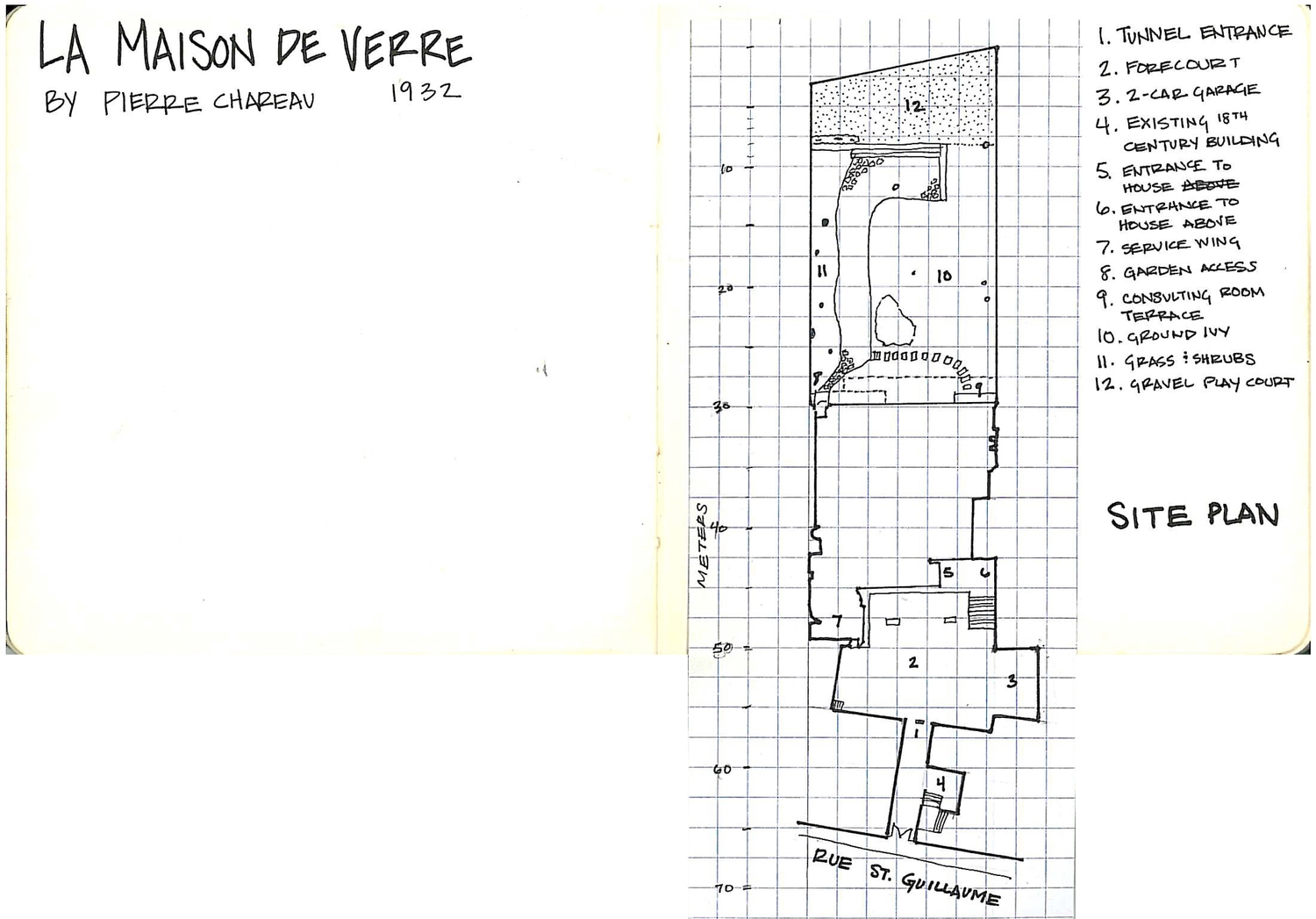

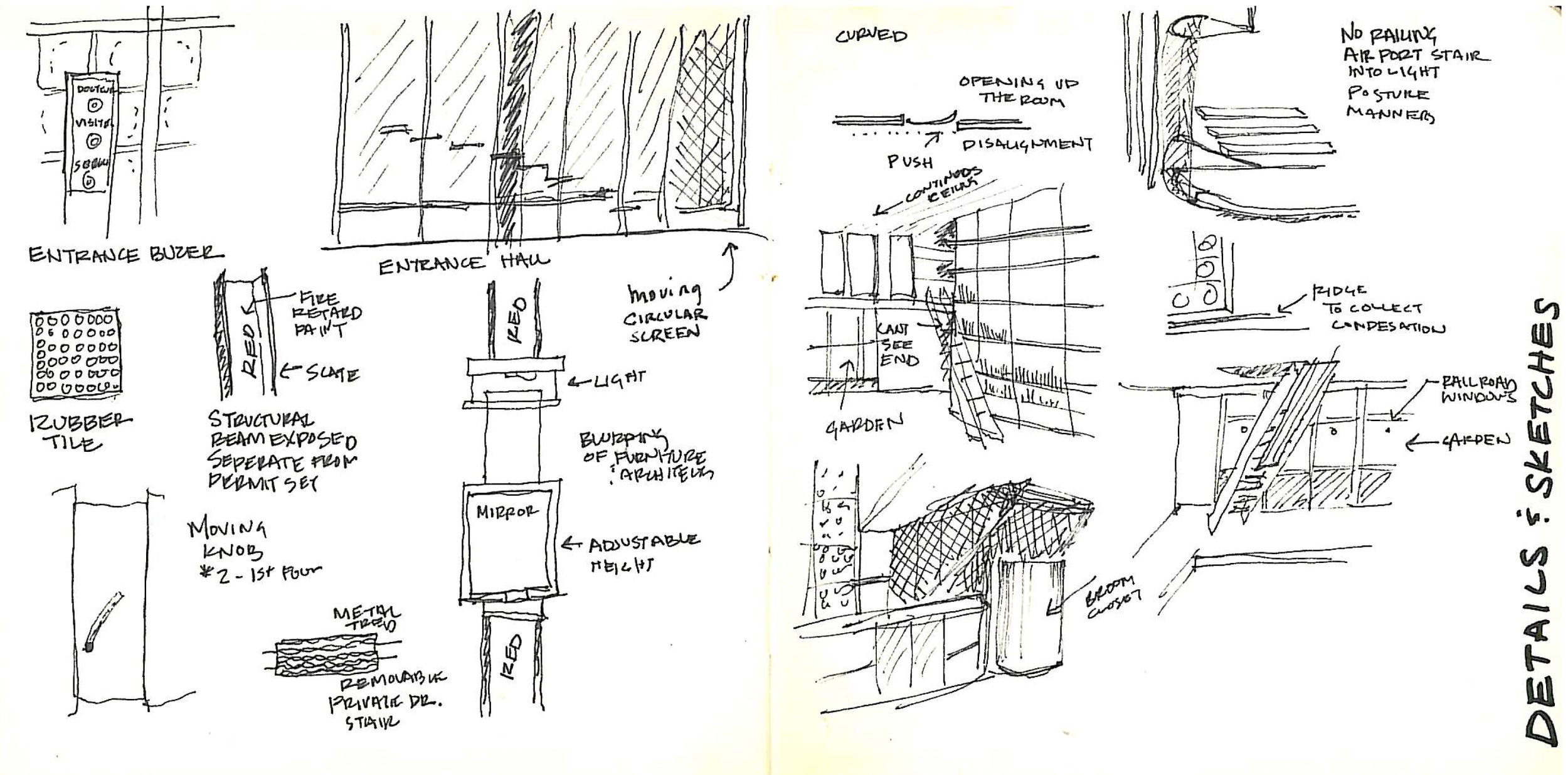

Paul Nelson, a contemporary of Chareau, articulates perfectly what I find so refreshing about this piece of early modernism. This is the farthest you can get from the modernist "object in the landscape" fetish; this building is all wrapped up in its urban context and cranky upstairs neighbors. The outcome was borne from a collaboration of the designer, architect, craftsmen, and the owners; where every aspect of function was studied, reviewed and designed for. These details weren't designed for aesthetic cohesion as in a Frank Lloyd Wright structure - they were designed to be solutions to specific habitational issues that the Dalsaces voiced. This is the epitome of "Integrated Project Delivery," decades before that term warranted invention. And the result? Functional beauty.

For further reading, I highly suggest The New York Times article "The Best House in Paris" by the (insanely lucky) architectural critic Nicolai Ouroussoff who was able to inhabit Maison de Verre and interview the new owner. If you are interested in seeing Maison de Verre in action, there is this delightfully French video complete with sepia 1930's style reenactment. Minute 12:00 shows the awesome exterior lighting and minute 20:00 to the end is a compilation of the intricate moving parts.

Maison de Verre's entrance and the post's author, back when she thought orange hair was cool.